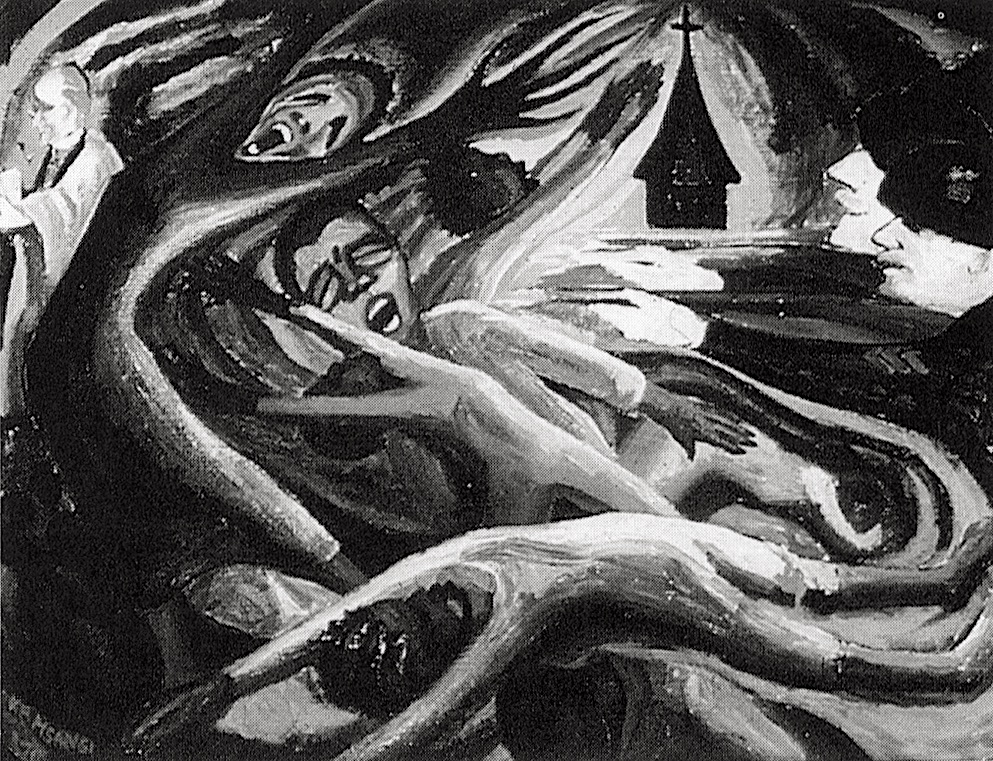

In Tanzania, the CEAA was acknowledged as an important agency linking the country’s new arts and cultural development programmes in the East African region. The birth of CEAA in 1964 was to some extent inspired by the Pan-Africanist movements at the Makerere University College in Kampala in the 1940s. African students studying abroad and within Africa were forerunners of Pan-African movements through various approaches. The CEAA found its roots in Tanzania through early fine art students, who became its members while studying at Makerere from the 1940s onwards. When East African countries such as Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania achieved independence in the early 1960s and later formed the East African Community in 1967, CEAA was already in place, with artists working in collaboration across their national frontiers FIG 01.

During the first CEAA meeting, Sam Ntiro was elected chairperson, Elimo Njau as its Secretary-General and Eli Kyeyune as its treasurer (Miller 1975:73). The School of Fine Arts at Makerere University in Kampala, apart from its continued tradition of providing art education to East African students, also provided space for visual art societies and group activities. CEAA chose Makerere as its regional headquarters, while creating branches for its members in their respective countries. In Tanzania, the CEAA branch office was situated in the Division of National and Antiquities at the Ministry of Education premises in Dar es Salaam. The CEAA was known from 1969 as the Society of East African Artists (SEAA), while Francis Musango from Kenya replaced Elimo Njau as its new Secretary General (Miller 1975:97).

Based on its founding objectives the CEAA intended to organise and coordinate projects to improve and promote visual arts activities in East African countries. The focus was to inspire young artists and join forces to localize visual art practices by incorporating a form and content style based on indigenous traditions within the East African region and Africa as a continent. Closer reviews of CEAA activities indicate that in many instances this organisation pioneered cultural decolonisation campaigns in the visual arts field. The Community in Tanzania significantly inspired and promoted the visual arts through training, exhibitions and conferences. Member artists volunteered to teach visual arts in secondary schools, teachers’ training colleges and later, when established, at the University of Dar es Salaam.

![[FIG 01] Unknown Artist, watercolour 1990s, Nyerere of Tanzania; Obote of Uganda; Kenyatta of Kenya, Photograph by Makukula, D., Courtesy Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation](https://eaman.belvadigital.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/FIG-01_03_-President-JNyerere_-Obote-of-Uganda_-_-Kenyatta-of-Kenya_Watercolour-painting_Unknown-artist-_early-1990s_Photograph-by-Makukula_courtesy-of-Mwalimu-Nyerere-Foundation_October-2015.png)