Ethiopia’s rich history is characterized by its ancient endogenous civilizations and religious traditions. These are passed on for generations through oral history and inscriptions of written languages. Ancient languages include Sabean, which is no longer in use; the Ge’ez now only used in the Ethiopian Orthodox Churches, Arabic in the Harari region for qur’anic worship and Amharic, which has been the official national language since the twelfth century. Due to geographical proximity various societies in Ethiopia are among the earliest to be exposed to and to accept both Christianity and Islam, in the 4th and 7th century respectively.

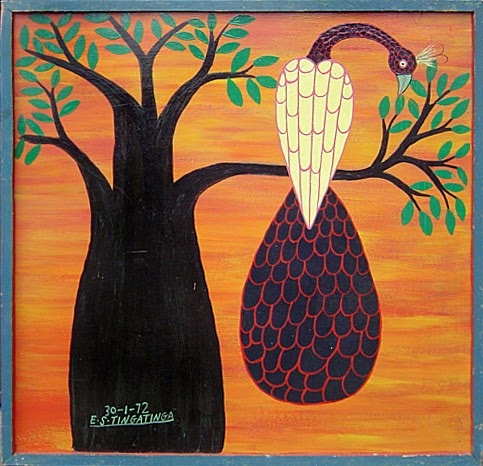

Both religions continued to evolve until modern and present-day Ethiopia with the unique particularities of the local interpretation of both religions. The emergence and expansion of these missionarising religions since the medieval periods is one facet of the recorded history of religions in Ethiopia. But various communities persisted in maintaining regional religious and cultural traditions, such as the practice of Waaqeffanna of the Oromo and their social ethics of Safuu, rather than adopting incoming religions and institutional politics. Peoples and ethnicities from the southern part of Ethiopia, for example the Konso people known for their sculpture known as Waka carved from wood, are also among many who maintained their indigenous beliefs and motifs. Attributable to its geographical set up in the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia’s encounters with foreign and colonial powers are a prominent part of its past. The settlement history of communities and ethnicities and their internal conflicts recurrently surfaced in power struggles and wars waged in the country. Dr Yerasework Kebede Hailu (2020) states that:

“Historically, Ethiopian identity has delineated from different perspectives: the Aksumite perspective, which presents an understanding of Ethiopia as an African Christian society; the Orientalist Semitic perspective, highlighting Ethiopia as Abyssinia; the Pan-Africanist, Garveyism and diasporic perspective, presenting Ethiopia as a symbol of African political freedom; and the Rastafarian perspective, featuring Ethiopia as the home of the Lion of Juda“ (Hailu, University of South Africa, 2020). These perspectives served as the fertile bedrocks for the existence of rich plural societal and national values. Endogenous spiritual aspirations were enriched by new religious traditions while patriotism mined legends from ancestral oral heritage. Traditional knowledge systems, drawn from regionally diverse cosmologies, converge in many of the local narratives, which play a significant role in shaping modern and modernist art in Ethiopia.